Texas’s Data Center Boom: A Thirsty Threat to the Lone Star State’s Future

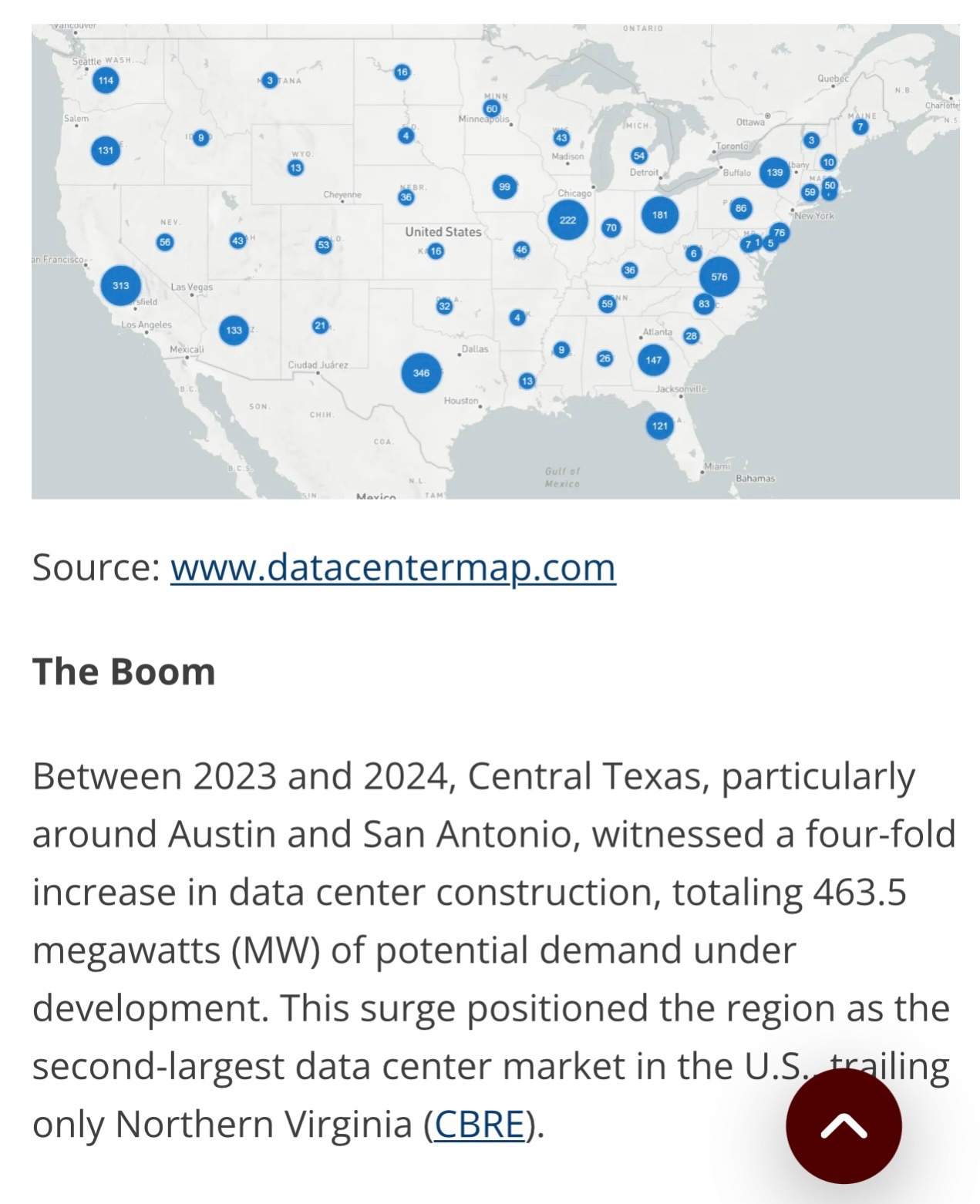

As of August 29, 2025, Texas stands at the forefront of a digital revolution, hosting over 378 data centers equipped for AI processing and cloud computing. With giants like Microsoft, Amazon, and emerging players like Vantage Data Centers pouring billions into expansive campuses—such as Vantage’s $25 billion, 1,200-acre “Frontier” project near Dallas—the state is poised to dominate the AI and data infrastructure landscape. However, this boom comes at a steep environmental and societal cost, particularly in water usage. Projections indicate data centers will consume 49 billion gallons of water in 2025, soaring to 399 billion gallons by 2030—nearly 7% of Texas’s total water supply. Amid persistent droughts and stressed aquifers, this insatiable thirst poses looming dangers: exacerbated water scarcity, failed desalination efforts, and a troubling trend of wealthy investors snapping up land for water rights to fuel these facilities. As residents face restrictions and drying wells, the unchecked expansion risks turning Texas’s tech dream into an ecological nightmare.

The Water Crisis: Data Centers’ Insatiable Demand

Texas’s data centers are guzzling water at an alarming rate, primarily for evaporative cooling systems that prevent servers from overheating. A single midsize facility uses about 300,000 gallons daily—equivalent to the consumption of 1,000 households—while larger ones can demand up to 4.5 million gallons. In San Antonio alone, two data centers operated by Microsoft and the U.S. Army Corps consumed 463 million gallons between 2023 and 2024, even as local residents endured Stage 3 drought restrictions limiting lawn watering to once a week. Statewide, these facilities withdraw mostly freshwater, with 80% evaporating and the rest discharged as salty wastewater, straining municipal treatment systems.

The challenges are multifaceted. Texas law prevents local authorities from regulating or even tracking data center water usage, leaving communities in the dark about the full impact. About 20% of U.S. data centers, including many in Texas, rely on watersheds under moderate to high stress from drought. This has led to real-world harms: in Georgia, a Meta data center caused nearby wells to fail and polluted water supplies with sediment, a scenario that could repeat in Texas’s high-stress areas. Rising temperatures exacerbate evaporation, and without mandates for recycled water or efficient cooling, data centers are “manufacturing water scarcity,” as critics put it.

Compounding the issue is the lack of transparency and policy oversight. Unlike electricity, where Senate Bill 6 allows curtailment during shortages, no equivalent exists for water, allowing unchecked growth amid a crisis where reservoirs like Corpus Christi’s sit at 29.9% capacity.

Desalination: A Failed Promise for Relief

In theory, desalination could alleviate Texas’s water woes by converting seawater into freshwater. The state has pursued projects like seawater desalination, with recommendations to produce 192,000 acre-feet per year by 2070 if all proposed plants are built. However, in practice, these efforts are mired in failures, high costs, and environmental pitfalls, offering little immediate help for data center demands.

Take Corpus Christi’s Inner Harbor desalination plant: Designed to drought-proof the city’s supply and support industrial needs, including potential data centers, the project has been paused indefinitely as of July 2025. Costs ballooned 60% to $1.2 billion from an initial $757 million estimate, prompting the City Council to delay decisions until at least August 26, 2025, amid uncertainty over reallocating $757 million in state loans from the Texas Water Development Board. The pause has halted work on a $12 million pilot plant and could lead to further cost increases, with engineering firm Kiewit warning of “serious losses.” Residential water bills could rise by $11 monthly, commercial by $206, and industrial by $463,000 by 2029, shifting the burden to ratepayers.

Environmental issues further doom desalination’s viability. Plants discharge concentrated brine—over 50 million gallons daily in Corpus Christi’s case—threatening coastal ecosystems and aquatic life. Texas has few regulations for brine disposal, raising concerns about long-term harm to bays and fisheries. Broader efforts, like Arlington lawmaker Tony Tinderholt’s push for a seawater desalination feasibility study, highlight the expense and environmental trade-offs, with no quick fixes in sight. As data centers proliferate, desalination’s failures mean no reliable alternative to depleting groundwater and surface water.

Billionaires and Investors: Scooping Up Land for Water Rights

Amid regulatory voids, a disturbing trend emerges: wealthy investors and billionaires buying vast tracts of land to secure water rights, potentially to supply data centers and other industries. This commodification of water treats it as an investment asset, exacerbating scarcity for locals.

In East Texas, Dallas millionaire and hedge fund manager Kyle Bass purchased over 11,000 acres across Anderson, Houston, and Henderson counties, planning to install more than 40 high-capacity wells to pump 16 billion gallons annually from the Carrizo-Wilcox aquifer for export to other parts of the state. While not explicitly tied to data centers, the project’s scale aligns with industrial demands, including tech infrastructure, and has drawn condemnation from East Texans worried about aquifer depletion and environmental harm.

This mirrors a national pattern where billionaires “buy” water through land acquisitions. In California, Stewart and Lynda Resnick of the Wonderful Company control a 57% stake in the Kern Water Bank, leveraging water rights for their 140,000-acre farming empire amid droughts. Investors like New York-based Water Asset Management own 3,000 acres in Colorado’s Grand Valley for water rights, while Harvard University has amassed $300 million in California vineyards tied to valuable water allocations. Greenstone Resource Partners flipped 500 acres in Arizona for a $14 million profit on water rights alone. In Texas, such moves risk creating “paper water”—rights exceeding actual supply—potentially leading to catastrophe as climate change intensifies scarcity.

Data center developers are following suit, with acquisitions like TCDC’s 235-acre purchase in Ector County for an AI facility, including a letter of intent for another 203 acres. Brokers are offering over 2,100 acres across Dallas and Fort Worth primed for data centers, often with water access in mind. This land grab prioritizes profit over sustainability, leaving communities with depleted resources and higher costs.

Larger Environmental and Community Impacts

Beyond water, data centers contribute to grid strain, with ERCOT projecting doubled demand by 2031, and environmental racism in areas like Corpus Christi’s Hillcrest neighborhood, where industrial pollution shortens life expectancy. Noise, light pollution, and wastewater harm wildlife and health, as seen in Hays County residents’ opposition to new facilities.

A Call for Urgent Action

Texas’s data center surge risks a water crisis of epic proportions, with desalination stalled by costs and environmental flaws, and water rights increasingly monopolized by the wealthy. Without regulations mandating tracking, recycled water use, or limits on consumption, the state gambles its future. Policymakers must act to protect this vital resource before the tech boom leaves Texans high and dry.